50% Rule: FEMA & NFIP Similarities And Differences, Is it Constitutional?

The 50% rule makes economic sense for FEMA, the NFIP, and its local insurance partners but is not conducive to the property owner making a rebuild next to impossible.

The 50% rule makes economic sense for FEMA, the NFIP, and its local insurance partners but is not conducive to the property owner making a rebuild next to impossible.

The 50% rule forces the property owner to either personally incur substantial structural upgrade costs in order to meet regulatory dictates or just simply walk away from the property. The second choice is to accept an acquisition buyout program and sell the land to a private entity or a municipality. Many acquisition buyout programs than deed the property over to a land trust which converts the land into green space in perpetuity rendering the property ineligible for future development.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency's (FEMA) 50% rule is a regulation that applies to flood-damaged structures within Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs). The rule states that if the cost to repair a damaged structure is more than 50% of the structure's market value, the structure is considered substantially damaged. In this case, the entire structure must be brought into compliance with current flood regulations before repairs can begin. This may include: Elevating the structure, Using flood-resistant materials, Proper flood venting, and Meeting stricter building codes.

Key Differences from NFIP 50% Substantial Damage Rule:

1). Program: The FEMA PA 50% Rule applies to the FEMA Public Assistance (PA) Grant Program, which helps communities and certain entities recover from disasters. The NFIP 50% rule is associated with the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which provides flood insurance to property owners.

2). Eligibility: The FEMA PA program assists with repairs to public infrastructure and essential services, not necessarily individual homes. The NFIP provides flood insurance for covered structures.

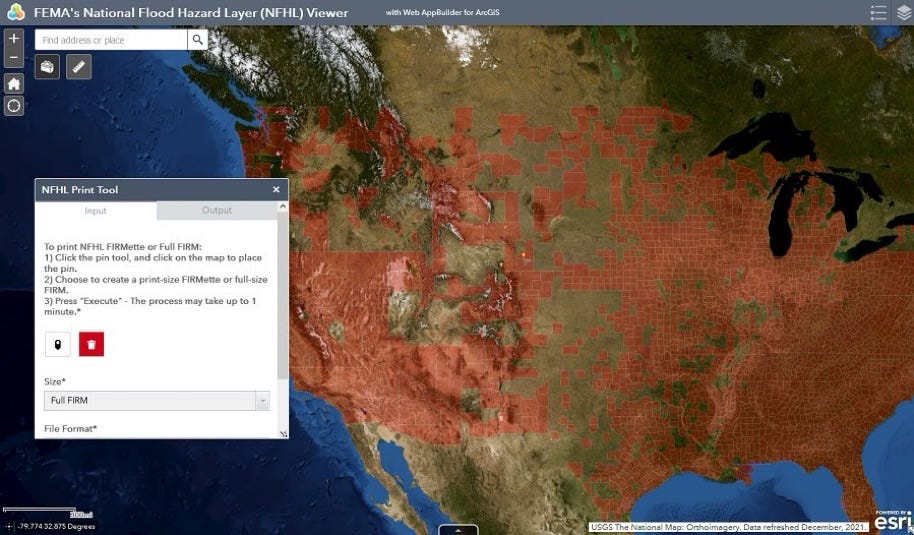

3). Trigger: The FEMA PA rule is triggered by any disaster, not just floods. The NFIP rule specifically applies to flood damage. The Federal Emergency Management Agency's (FEMA) National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is over $20 billion in debt. The estimated annual cost of flooding today is over US$32 billion nationwide, with an outsized burden on communities in Appalachia, the Gulf Coast and the Northwest.

Many legal scholars are asking whether the new FEMA rules are a violation of the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause? Others argue the right to Due Process under the 14th Amendment has been subverted by what is referred to as “eminent domain regulatory capture”: “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Supreme Court Grants New Takings Clause Case

Petitioner Bowers Development, LLC, was under contract to buy land in upstate New York in the hopes of building a medical office building. Then the local government condemned that land for the express purpose of giving it to a different private corporation—one that was building a different medical office building and had asked for the Bowers land to use as its private parking lot. These facts are uncontested and were accepted by the New York Court of Appeals.

The question presented to the Court is whether this is allowed under the Public Use Clause. More specifically: Bowers Development was under contract to buy a lot in Utica, NY, near a newly built private hospital, which it thought would be a good site for a new medical-office building. But that plan never came to fruition because of Respondent Central Utica Building, LLC, which also had plans “to build a medical office building[,] on an adjoining property.”

The Takings Clause Incidental Economic Question

In the 20 years since Kelo was decided, private-to-private condemnations have continued to create controversy and injustice—originally nationwide and now, regularly, in the states that have not limited Kelo under state law. The inability of courts to apply Kelo’s purported limitations has caused confusion for litigants and courts alike. And the decision has continued to receive sharp criticism from both legal scholars and Members of this Court.

That makes it exactly the sort of A to B transfer from one private property owner to another private property owner for economic development under a vague and ambiguous definition of public use by either city planners are government private-public partnerships -- justified only by the assertion of incidental benefits.

Current strategic buyout acquistion programs offer home owners that fall in FEMA floodplain zones substantially larger sums of money to sell than if they decide to rebuild on the property. Is this an incidental public use Takings as argued by Justice Connor and Justice Thomas?

Hopefully a narrowly defined Takings Test will be properly addressed at the Supreme Court. If a new Takings Test is established with more stringent guidelines, it should help elucidate when a private-public partnership buyout acquisition contract agreement is legal and appropriate.

All my research and writings is out love of country and my fellow patriots. My purpose is to educate the public on government overreach and to help build back our country to the original principles of our founding fathers. Please consider a paid subscription or a one time donation to my buymeacoffee account and help support my efforts.

“When is it ok for government planners to priotize projects over individual property owners -- respecting private property owners is essential to a free, just and prosperous society?”

The question presented is also important. In the 20 years since Kelo was decided, private-to-private condemnations have continued to create controversy and injustice—originally nationwide and now, regularly, in the states that have not limited Kelo under state law. The inability of courts to apply Kelo’s purported limitations has caused confusion for litigants and courts alike. And the decision has continued to receive sharp criticism from both legal scholars and Members of this Court.

That makes it exactly the sort of A to B transfer from one private property owner to another private property owner for economic development under a vague and ambiguous definition of public use by either city planners are government private-public partnerships -- justified only by the assertion of incidental benefits.

Is this an incidental public use under the Takings Clause as argued by Justice Connor and Justice Thomas?

Current strategic buyout acquistion programs offer home owners that fall in FEMA floodplain zones substantially larger sums of money to sell than if they decide to rebuild on the property.

Hopefully a narrowly defined Takings Test will be properly addressed at the Supreme Court with the upcoming Bowers Development case. If a narrowly defined new Takings Test is defined at the Supreme Court, it should help elucidate when private-public partnership programs are appropriately applied to natural disaster, mitigation, planning and recovery. And when is it proper for another private entity to purchase a private property with federal matching grant money after a regulatory body has determined the property is substantially damaged after a natural disaster?

Specifically, under the original intent of the Takings Clause, government’s authority to seize private property and provide just compensation for “Public Interest” is explained below:

The Takings Clause was to require the government to compensate property owners when it physically took their private property for public use, essentially only applying to direct physical appropriation of land and not to government regulations that might dimish property value, even significantly: meaning the

focus was on situtations like building a road or fort on someone’s land and taking ownership of it, not on zoning laws or other regulatory restrictions.

The primary understanding was that the clause only applied when the government physically seized property, not when it simply regulated its use.

When is it ok for government planners to priotize projects over individual property owners -- respecting private property owners is essential to a free, just and prosperous society.

The ”Kennedy” show on Fox Business has a great short concise discussing the unconstitional nature of the Kelo decision.